Only 16% of areas with high richness of large marine vertebrates are protected from maritime traffic

The research lays the groundwork for developing policies that sustainably address the ecological challenges posed by maritime transport.

Humpback whale near a vessel. The escalation in global maritime traffic increases the risk of collisions and disturbances to marine wildlife. / Alan Bedding / Pixabay

Steady growth in global maritime traffic is posing an increasing number of threats to marine biodiversity, including pollution, vessel strikes and disruptions to species’ behavior. In this context, a research team led by the University of Algarve (Portugal), with participation from the Doñana Biological Station of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), has revealed major gaps in the coverage of Marine Protected Areas and highlighted the need to strengthen conservation measures.

The study, published in Biological Conservation, details a global analysis that identified regions where high species richness —such as whales, seals, turtles and seabirds—coexist with either intense or minimal shipping activity.

Protection gaps in the world’s oceans

Around 90% of all internationally traded goods are shipped by sea. Beyond its economic significance, maritime transport is vital for food security, energy distribution and access to essential goods. However, it can have negative impacts on marine ecosystems, particularly on large animals.

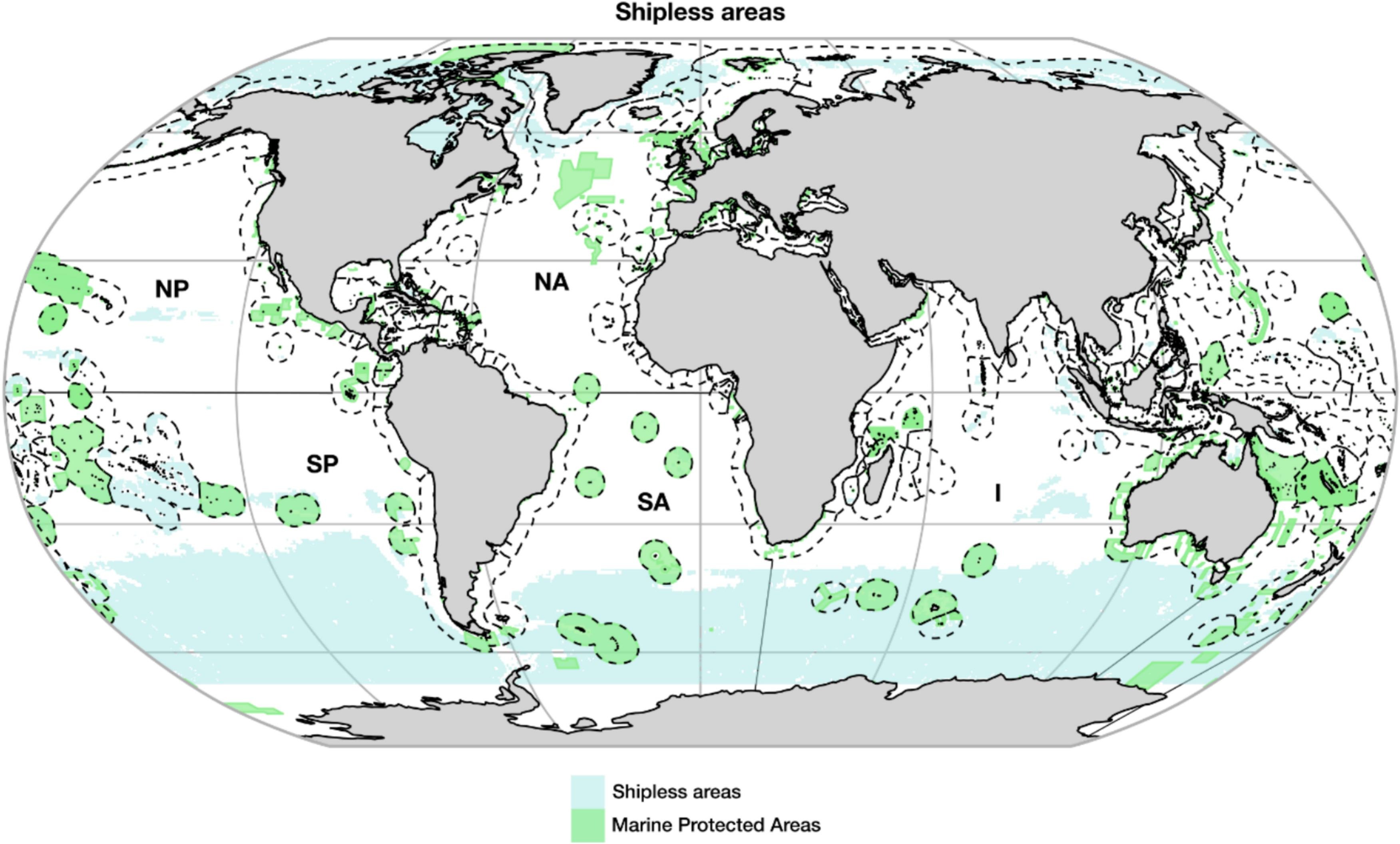

To better understand where and how these impacts occur, the team identified regions where high species richness overlaps with high, low or nonexistent maritime traffic.

Areas where large numbers of species coincide with heavy shipping are mainly concentrated in coastal zones, especially in the central Pacific, the southern Indian Ocean and the South Atlantic. These zones were classified as Priority Mitigation Areas, meaning regions where the impacts of maritime activity must be reduced. In Spain’s case, the entire Atlantic coast falls within this category.

Conversely, areas with high species density but low maritime traffic are found mostly in the higher latitudes of the Southern Hemisphere, where human presence is limited. These were designated Priority Preservation Areas, regions that should be reserved to protect their biodiversity. Finally, areas without maritime traffic are located largely in polar regions and remote oceanic areas.

However, only a small portion of these three types of regions currently enjoys any form of protection. In shipless areas, Marine Protected Areas cover just 12%. Priority Preservation Areas—where biodiversity is high and traffic risk is low—are protected at a rate of 15%, while Priority Mitigation Areas—where high biodiversity and intense traffic coincide—reach 16% protection.

Zones with full bans on extractive activities such as fishing are even scarcer: 6.8% in shipless areas, 9.5% in Priority Preservation Areas and 5.6% in Priority Mitigation Areas.

“These data reveal significant gaps in the protection of marine biodiversity and underscore the urgent need to reinforce conservation measures and spatial planning for maritime traffic on a global scale,” explains Marcello D’Amico, a researcher at EBD-CSIC.

Policies for better conservation

The study lays the groundwork for crafting policies to address the ecological challenges of maritime transport and help meet the 30x30 target, which aims to protect 30% of marine areas by 2030. “Identifying zones with low shipping activity and areas where biodiversity overlaps with dense traffic provides an objective foundation for guiding marine spatial planning and management decisions,” D’Amico adds.

The researchers recommend formally designating areas with low or zero shipping activity and high biodiversity, and prioritizing their inclusion in networks of Marine Protected Areas. For regions with intense maritime activity, the team proposes targeted strategies to mitigate impacts, such as reducing vessel speeds—lowering underwater noise and collision risks—and optimizing shipping routes to avoid the most sensitive zones.

This work forms part of a broader research program at the Doñana Biological Station examining how infrastructure affects biodiversity. This experience has enabled the team to apply knowledge gained from terrestrial impacts to the marine realm, advancing the perspective that maritime traffic should be considered another form of infrastructure with significant environmental effects.

“We want to highlight the value of this study as an example of how conceptual frameworks developed in terrestrial ecology can be successfully applied to marine environments. Integrating these disciplines allows for a more comprehensive approach to understanding how transportation affects biodiversity, regardless of the setting. The study also reinforces the importance of international collaboration and the use of open global data to move toward more coherent and sustainable ocean management,” D’Amico concludes.

The research also involved the Centre for Marine Sciences of the Algarve, Nord University, the University of Évora and the University of Lisbon.

Reference

Mestre, F., D'Amico, M., Bastazini, V.A.G., Assis, J., Jacinto D., Marçalo, A., Ascensão, F. Mapping global shipless areas and conflict zones between shipping and large marine vertebrates. Biological Conservation. DOI: 10.1016/j.biocon.2025.111431.

Comunicación

Estación Biológica de Doñana - CSIC