Historical documents preserve the evidence of the introduction of crayfish in Spain in the 16th century

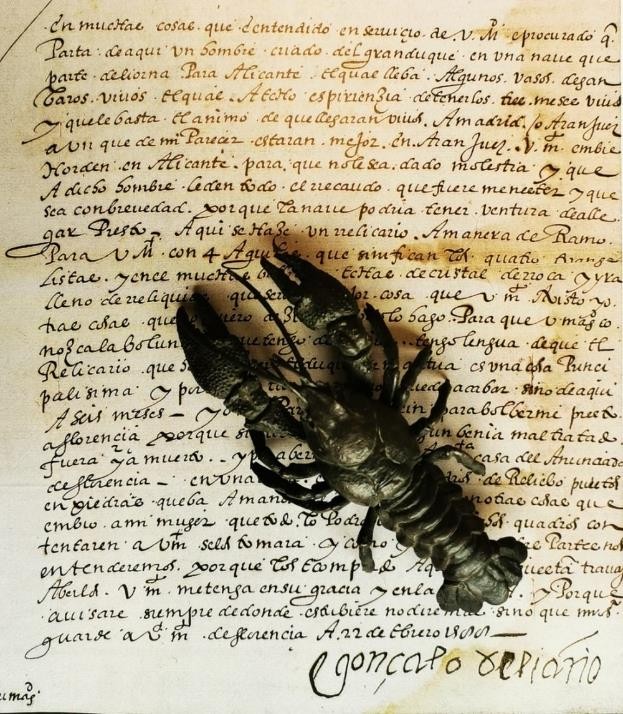

Metal sculpture of an Italian crayfish, Austropotamobius fulcisianus, placed on a copy of the February 1588 document reporting to King Philip II on the shipment of this species from Tuscany

A 16th-century document has confirmed, for the first time, the successful introduction of the Italian crayfish into Spain in 1588. The discovery stemmed from a chance encounter on social media between researchers from the Doñana Biological Station (EBD-CSIC) and the University of Murcia, and has led to a new study that carefully reconstructs the entire process. The recently published work in the journal Biological Conservation highlights the value of interdisciplinary research for long-term understanding of biodiversity.

The many historical documents examined shed light on the motivations, arrangements, and people involved, while allowing the researchers to pinpoint both the origin (Tuscany) and the exact timing of the introduction (early 1588). Remarkably, this introduction that occurred more than 400 years ago is now better documented than most contemporary introductions. The study, recently published in Biological Conservation, highlights the value of interdisciplinary research for understanding biodiversity over the long term.

A non-so native crayfish

“Discovering the vast amount of biodiversity information hidden in historical archives was a real surprise and opened up a fascinating range of new research opportunities,” says Miguel Clavero, lead author of the study. For over a decade, this researcher has been studying the historical presence of crayfish in the Iberian Peninsula, showing that the species long believed to be native was in fact imported from Italy in the 16th century. The work carried out at the Doñana Biological Station (CSIC) has traced changes in the distribution, ecological niche, and use of the Italian crayfish over the centuries, drawing on a wide variety of sources, from geographical dictionaries to historical newspapers.

“Over the years, we have come across documents detailing the efforts made by Philip II’s court to acquire crayfish and other exotic animals to populate these ponds,” Clavero explains. In the early years of his reign, King Philip II undertook an ambitious project to landscape the Royal Sites, which included the construction of ponds inspired by those he had seen in the Netherlands. “At that time, there were no crayfish in Spain, and keeping them in his gardens was part of the monarch’s aura of exclusivity,” he adds.

Until now, however, no documents had been found proving that the introduction was successful—that is, that Italian crayfish actually reached the Royal Sites. “The new document presented in this article records a payment of 300 ducats, ordered directly by Philip II, to Antonio de Ugnano, servant of Grand Duke Ferdinando I, who had managed to bring live crayfish all the way to Madrid—a feat no one had accomplished until then,” explains Alicia Sempere, a researcher at the University of Murcia and co-author of the study. “It was an enormous sum, equivalent at the time to the annual salary of a physician or the value of 75 pigs, which shows both the king’s eagerness to obtain the crayfish and his satisfaction at having succeeded,” she adds.

The historical records gathered cover a 25-year period, from 1563 to 1588 and were preserved in different Spanish archives—particularly the General Archive of Simancas in Valladolid. The documents describe Philip II’s desire to receive the crayfish, the instructions issued to search for them and prepare for their expected arrival, the failure of several early attempts, and finally the shipment sent from Tuscany in February 1588.

A chance encounter completed the story

The newly published study can truly be considered a product of serendipity, born from chance and an unexpected twist. In December 2024, the Doñana Biological Station (CSIC) released the documentary El cangrejo del rey (The King’s Crayfish), freely available for viewing, which explores the history of crayfish in Spain. Several social media accounts picked up on it. “One of them posted about the shipment of crayfish from Tuscany, using their Italian name (gámbaros). At that moment, I remembered having taken notes from a document that mentioned it, so I replied by reproducing parts of the text,” recalls Alicia Sempere.

“Reading it made my heart skip a beat,” remembers Miguel Clavero. “What Alicia had transcribed was proof that the crayfish sent from Tuscany had indeed arrived alive in Madrid—the missing piece needed to complete the puzzle of this historical introduction.” The two researchers immediately got in touch and began the collaboration that has now led to the newly published article. The work reviews and summarizes all the historical information known to date and caps it off with the new document.

“I might not have paid attention to the document mentioning crayfish, since it didn’t really fit within my main research lines. And I might not have written the post—or Miguel might not have noticed it,” says Alicia Sempere. “It’s fascinating how a casual encounter on social media gave rise to new knowledge that is not only historically interesting, but also has implications for biodiversity management today,” Clavero confirms.

Protecting an introduced species

In 2024, Spain’s Ministry for Ecological Transition and Demographic Challenge approved the Strategy for the Conservation of the Iberian Crayfish (Austropotamobius pallipes) in Spain. This legal framework sets out “the basic lines of action and the measures to be applied for the conservation of the species in Spain.” But for Miguel Clavero, the document is problematic because it refers to a species, Austropotamobius pallipes, that is not actually found in Spain. “It’s absurd,” he argues. “Pallipes and fulcisianus are very ancient lineages that diverged more than 10 million years ago. Moreover, the strategy repeatedly claims that what it calls the Iberian crayfish is a native species of Spanish fauna—contradicting the historical, genetic, and biogeographic evidence.”

For Clavero, the problem lies in the fact that different administrations—both the ministry and the regional governments—tend to follow long-standing routines. “They are very resistant to change, largely because in every administration there are people who have spent decades working on crayfish conservation and have made the species the center of their professional activity, and I would even say of their emotional universe,” Clavero observes.

However, the researcher emphasizes that these personal connections to the species should not compromise the need for natural resource management to incorporate the available scientific knowledge. “Given what we know, it makes no sense for administrations to continue treating the Italian crayfish, an introduced species, as one of their conservation priorities. It’s time to rethink strategies,” Clavero concludes.

Understanding how biodiversity was distributed in the past is essential for assessing and valuing the changes caused by human activity, as well as for setting conservation and restoration goals. However, those who study biodiversity often overlook the sources of information that make long-term knowledge possible. Conversely, historians familiar with archival research may not always recognize the significance of references to fauna and flora in these documents. In this context, collaboration across disciplines is indispensable to generate new knowledge.

Scientific reference

Clavero, M., Sempera Marín, A. (2025) Effective cooperation between ecologists and historians for conservation: documenting a 16th century crayfish introduction. Biological Conservation https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2025.111405