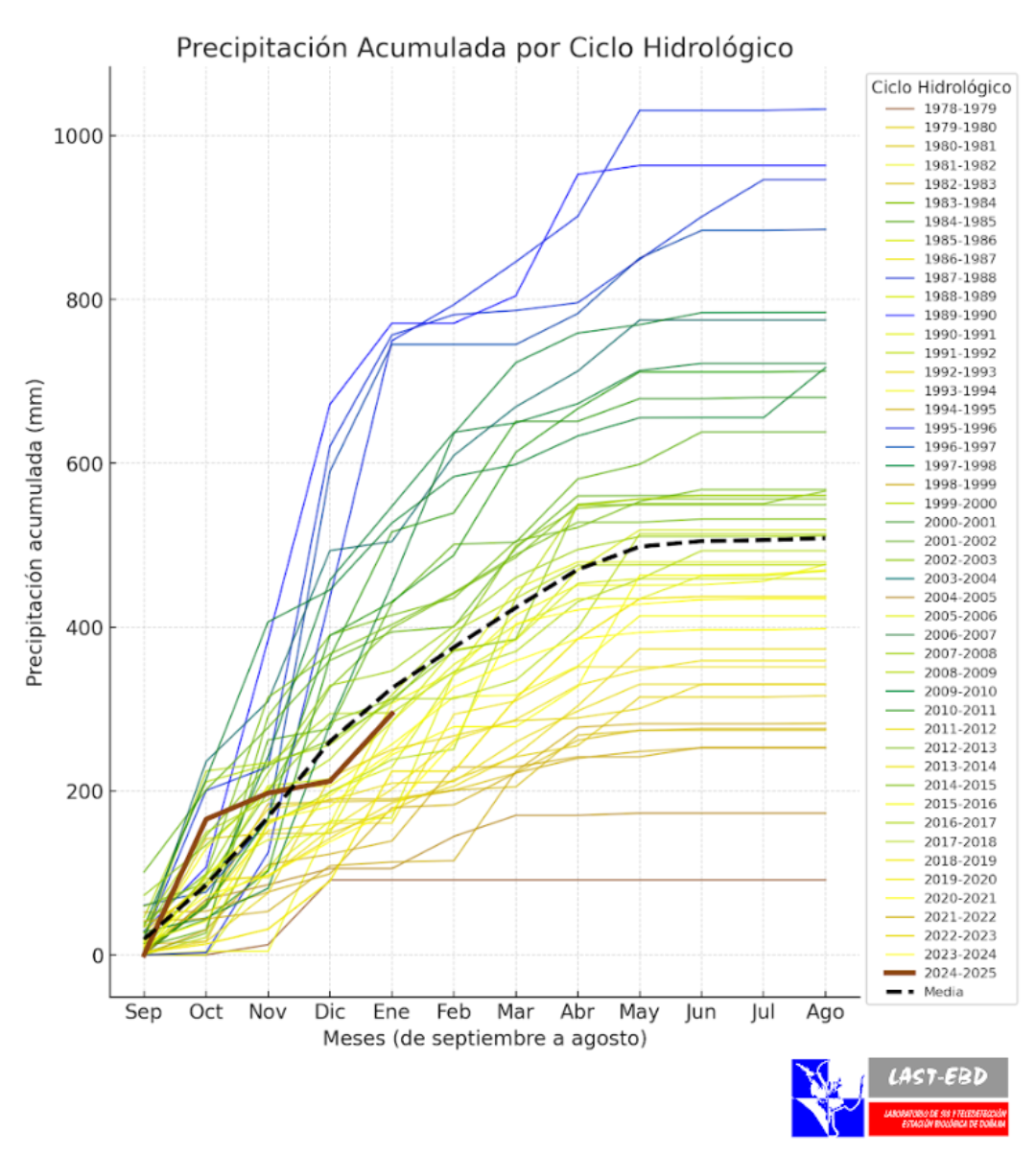

Doñana recoge 300 mm de lluvias desde septiembre, pero se tendrían que suceder años húmedos para compensar el déficit hídrico actual

Los valores de precipitación se encuentran en la media de invierno en Doñana. La marisma presenta una lámina de agua extensa y aceptable, con alrededor de 16.000 ha inundadas, aunque poco profunda para estas fechas.

Comparación del estado de Doñana a vista del satélite Sentinel-2 de los días 15 de enero (izquierda) y 4 de febrero (derecha) de 2025. // EBD-CSIC

Desde septiembre, se han registrado 300 mm de precipitaciones en la estación manual del Palacio de Doñana, en el corazón del Parque Nacional. Esta cifra supera la media de los últimos diez años, pero se encuentra entre los valores promedio de un invierno en Doñana. La lámina de agua de la marisma es extensa, con alrededor de 16.000 hectáreas inundadas, aunque poco profunda para lo que es habitual en estas fechas.

El año hidrológico, que se cuenta de septiembre a agosto, comenzó con buenas precipitaciones en octubre, seguido de un noviembre y diciembre secos que dejaron a Doñana con escasa agua al inicio del invierno. No obstante, las lluvias de enero han posibilitado que los niveles de precipitación se sitúen en la actualidad cerca de la media histórica.

En un ciclo normal, durante el verano, la falta de precipitaciones y las altas temperaturas secan la marisma, que no vuelven a inundarse hasta la llegada de las lluvias en otoño e invierno. Las marismas se asientan sobre un sustrato arcilloso, que necesitan, tras el periodo estival, volver a hidratarse para coger agua de nuevo. Se estima que se necesitan alrededor de 200 mm de precipitación acumulada para que las marismas comiencen a inundarse.

De hecho, antes de las lluvias de finales enero la inundación de la marisma se limitaba a zonas como la Madre del Rocío, Caño de las Madres y Lucios del Caballero, Vetalengua y Membrillo, que suelen ser las primeras en inundarse con las primeras lluvias. El hecho destacable de este año frente a años anteriores es que ha habido registros superiores a los 100 mm en el mes de enero, lo que unido a la precipitación anterior ha hecho que se active el sistema hidrológico al completo. Los arroyos de los Sotos, La Rocina, La Cigüeña y del río Guadiamar contribuyen al llenado con aguas fluviales, y no exclusivamente pluviales, de la marisma. En la actualidad, la lámina de agua de la marisma cuenta con una extensión amplia, en torno a las 16.000 hectáreas, según datos del Laboratorio SIG y Teledetección de la Estación Biológica de Doñana - CSIC.

Las zonas inundadas son principalmente la zona Norte y centro de la marisma de Hinojos (marisma Gallega) y Aznalcázar (marismas del Travieso). Sin embargo, aunque extensa, la lámina sigue siendo poco profunda. La estación hidrometeorológica Honduras del Burro indica una profundidad de en torno a 37,5 centímetros, Guadiamar Millán tiene 20 centímetros y Vetalengua, sobre 20 cm, por debajo de lo habitual para estas fechas.

Los datos de la ICTS Doñana, dependiente de la Estación Biológica de Doñana - CSIC, indican que, a pesar de que las lluvias registradas hasta ahora se aproximan a la media de la última década, siguen siendo insuficientes. Esto se debe a un gran déficit hídrico, lo que impide que la marisma se inunde hasta el nivel promedio habitual del invierno. Abel Valero, responsable técnico de la Infraestructura y Servicios de las Tecnologías de la Información de la Reserva Biológica de Doñana, señala que “no ha llovido tanto como parece. Además, partimos de una situación de déficit. Para que se vuelva a restituir el normal funcionamiento de los ecosistemas, tiene que haber un superávit muy grande, es decir, años húmedos por encima de la media, así como reducir las extracciones del acuífero, que está sobreexplotado”.

También es importante destacar que en Doñana los frentes que proceden del Atlántico suelen dejar menos lluvias en las marismas. Las precipitaciones suelen ser mayores en la corona norte y el litoral que en el corazón de la marisma del Espacio Natural. Esta variabilidad se refleja en los datos: mientras que en la estación del Palacio de Doñana se ha registrado 300 litros por metro cuadrado desde septiembre, en otras estaciones de municipios de alrededor, como Moguer, se han registrado más de 450 litros por metro cuadrado.

Un gran déficit hídrico

“La importancia de Doñana está en su agua. Sin agua, Doñana no tiene vida”, explica Javier Bustamante, vicedirector de la Estación Biológica de Doñana y responsable de la ICTS Doñana. Debido al periodo seco que atraviesa el espacio natural en los últimos años y a la gran demanda de agua, que supera la carga anual, el nivel del acuífero desciende y las lagunas y manantiales naturales de Doñana, que aportan agua desde las dunas, se están perdiendo. En contextos de déficit hídrico, la biodiversidad de Doñana depende más del acuífero, que comprende casi 200.000 hectáreas de terreno y que excede por mucho la extensión del espacio protegido. Sin embargo, el nivel freático continúa en mínimos histórico, lo cual repercute también enormemente sobre la calidad de las aguas del acuífero.

El pasado informe presentado por la Conferencia Hidrográfica del Guadalquivir declara que tres de las cinco masas de agua del acuífero del entorno de Doñana están en riesgo de no alcanzar un buen estado. Así, por ejemplo, el piezómetro del carril del Corte registra una bajada de 1,61 metros en los últimos cuatro años. Este descenso afecta gravemente al sistema de lagunas de Doñana, el más dependiente del agua del acuífero, y ha provocado incluso, que la laguna de Santa Olalla, la más grande del Parque, se secara en los tres últimos años. Este impacto es significativo desde el punto de vista biológico: históricamente, Santa Olalla era una laguna permanente y en los últimos 45 años solo se había secado un par de ocasiones en años aislados. En la laguna se han llevado a cabo censos de aves históricos en verano, en los meses de julio y agosto, cuando se hallaba un elevado grado de biodiversidad, dado que era un refugio estival para muchas comunidades de aves, anfibios, peces y otras especies.

Otra de las consecuencias es el estrés hídrico que sufren la vegetación, especialmente el alcornoque, cuyas pajareras han sido una de las imágenes del parque que han dado la vuelta al mundo. “Esa comunidad de árboles se está secando”, afirma Bustamante.

Doñana corre el riesgo de convertirse en un complejo endorreico, es decir, una zona sin influencia de ríos ni del mar. La importancia de sus marismas para la biodiversidad depende fundamentalmente del aporte hídrico que reciben desde los arroyos vertientes y fundamentalmente del Guadiamar, cuyo brazo principal, el Caño Guadiamar está desconectado de la marisma desde mediados del siglo pasado. Es por ello que la reconexión y la restauración asociada del Caño Guadiamar son fundamentales para asegurar el futuro de Doñana. Dichas actuaciones están incluidas en el Marco de Actuaciones del Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y Reto Demográfico y la Junta de Andalucía.

La monitorización ambiental de Doñana

Ricardo Díaz-Delgado, coordinador de la Monitorización Ambiental de la ICTS Doñana explica: “En Doñana, la ICTS monitoriza, mediante instrumentos fijos en campo, la meteorología y la hidrología, de manera que vemos la información en tiempo real. La importancia de este seguimiento automático radica en conocer cuándo y dónde se producen cambios, lo que permite rápidamente avisar al equipo gestor para la toma de decisiones”. Los sensores en campo de la ICTS Doñana miden por ejemplo el nivel de agua de la marisma cada cinco minutos. Esta medición se realiza también de forma "manual" cada quince días, momento en el que además se efectúa el mantenimiento y calibración de los sensores. De esta forma, se pueden observar las fluctuaciones y cambios meteorológicos, ambientales y biológicos.

La Infraestructura Científico-Técnica Singular Reserva Biológica de Doñana (ICTS Doñana) nace en 2006 con el objetivo de brindar acceso y apoyo a la investigación en Doñana, así como desarrollar e implementar infraestructuras que permitiesen el control automatizado de su vida silvestre y sus ecosistemas.

Desde ese momento, se despliega una red de radiocomunicaciones y wifi que abarca la Reserva Biológica, el parque Nacional y parte del Parque Natural para el seguimiento automático de variables ambientales: hidrología y calidad de aguas, meteorología, gases de efecto invernadero, piezometría, cámaras e información multimedia. Esta red permite la conexión en tiempo real de la instrumentación y sensores desplegados en campo, así como el vuelco de la información generada en internet. Siempre a la vanguardia, la ICTS Doñana trabaja en la creación de un ‘Smart Environment’, es decir, una red ubicua de Internet de las Cosas que complementa la red de radio y wifi actual.